Lessons Learned While Making My Game

Overview

I’ve been working on a Tabletop Role Playing Game (TTRPG) for years now. It’s been a very educational experience, and I wanted to share some of the non-obvious lessons about game design that I’ve learned along the way.

There’s a lot of stuff here, and many examples. Please skip anything you already know, or isn’t interesting to you. This as a skatter-shot of random learnings, not a homework assignment. 😉

🙇♀️ Disclaimer: this could really use a good editing pass, but after writing so much I needed a break. I’d rather you have it unedited then have it sit on my computer for months.

Background

Before we dig into this, there are some things you need to know about me in order to understand the context I’m coming from.

- I’m a “frustration driven developer”. Using a thing with obvious flaws drives me buggy and makes me want to fix it.

- I love game mechanics.

- I love reading other people’s RPGs and learning how they approached different gaming problems.

- I’m absolutely not interested in making “a better D&D”.

- I’m only mediocre at creating settings.

I’ve been working on this game for years, not because I’m polishing my “perfect” game. It’s taken so long, because I’ve learned so much along the way, and had to restart from scratch so many times. It doesn’t help that there are so many wonderful games out there that made me feel like “yes! like that!” and want to throw out whatever core mechanic I had.

The Big Three (+1) Questions

Jared Sorenson is credited with “The Big Three Questions”

- What Is your Game About?

- How Does it Go about That?

- What Behaviors does it reward and/or encourage?

The +1 question is “How do you make that fun?” I don’t know who added it.

Search for his name and “The Big Three Questions” and you’ll find plenty of details about using them. I think that having answers to all of those is critical to designing a good game. The +1 question is very subjective. At the same time I believe that it’s really important to have a strong opinion on it while designing.

It’s important to have answers to The Big Three Questions as you set out. That answer may be just a strong feeling, a specific direction to explore, but it needs to be something.

What’s Your Game About?

There are many different people advising that it’s important to know what your game is trying to be, or what kind of stories it’s trying to tell. They’re right, but I have a more practical take on why.

What your game cares about, and the kind of experience it’s trying to provide, can not be delivered with a core mechanic that doesn’t support that.

If you don’t know what kind of stories you’re trying to tell with your game then you should really pause and ask yourself why you’re making one.

If you just don’t like the way your current game handles something, then just homebrew a solution for that. You don’t need to make a whole game.

In my mind there are two reasons to make a new game:

- I want to tell a particular story that no-one else is telling.

- I want a game with a particular perspective and/or vibe that I can’t get elsewhere, and can’t achieve by simply creating a new setting.

A lot of folks keep wanting to make new “generic systems” which can tell “any” kind of story. Please, don’t. We have enough1, and more importantly every well designed game that’s trying to tell a particular kind of story with a particular vibe, is going to do a radically better job than a generic game system used to do the same thing.

Core Mechanics Supporting the Story:

Powered By the Apocalypse (PbtA) games care about emphasizing significant moments, and complicating characters lives in interesting ways. It’s one of the best examples of mechanics clearly supporting the story.

PbtA games specifically don’t care about any decisions your characters make that don’t directly contribute to the type of story they’re going to tell. You only roll if there’s an applicable Move2. If there’s no move, you don’t need to roll. If there’s no move, the game doesn’t consider what you’re doing to be important to its goals.

There are generally only 3 outcomes too: success, success with complication, or failure, and you’re way more likely to get a complicated success than a simple success. This is the game saying that it doesn’t care a lot about simple success or failure, but that it likes stories with complicated, and messy progress.

If you don’t know that “complicated, and messy progress” is what you want, you can’t make a core mechanic that supports that, and your game will only feel “right” if you lucked out in your initial choice.

PbtA games only have story supporting mechanics. They don’t have mini-games. They don’t generally have much in the way of sub-systems. They not only have story supporting mechanics, they don’t tend to have any mechanics that don’t directly support the story. This is what we should all be striving for. Obviously some games need more complexity, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with having sub-systems, but we need to focus on throwing out everything that we can that isn’t absolutely necessary to tell the stories we want to tell.

That, but with a twist

Sometimes you love a game, but it’s fails to do something that’s important to you.

The core mechanic of Ironsworn, and by extension Starforged, tells us that Shawn Tomkin wasn’t satisfied with the simple successes and failures of PbtA. It tells us that he likes it when a story has the occasional dramatic successes and failures, but that he still likes “moves”. So, he came up with a core mechanic that combined all of that.

If that was all Sean cared about it could have just been a homebrew rolling variant with guidelines for handling critical success and failure with the existing moves. Fortunately for us, he had other things to say too.

No, less.

A common problem of new game designers is the desire to put ALL of their ideas into one place. Even if your ideas are all great, it’s rarely a good idea to try and combine them all in one place.

I heard someone on a podcast say something like “your first game is five games”. I think that’s true, and a lot of the time I think that’s because we have five games worth of ideas that we’re trying to shove into one game.

Personal Example

I hate the idea that magic users can bend reality with no cost or consequences to doing so. I think that altering reality should hurt. It should drain you. I think that sometimes, casting a spell should go horribly wrong in unpredictable ways3.

It’s not hard to address all of those. You take stress / harm when you cast. You roll on a random table when you have a critical failure, and something bad happens to you or your friends4.

As much as I loved that, I ultimately had to throw most of it out, because I’m not trying to tell a gritty story about powerful magics, and violent high-magic encounters. The only part that’s survived is the idea that casting spells is mentally draining.

It’s not about that.

Maybe this is a me problem, but each iteration of my game has changed, refined, and/or refocused what the game was about.

When I started working on my game I was enamored with ICRPG. It was just going to be a hack for the magic system. But, the more I wrote, the more I realized that while ICRPG is a wonderful game, with lots to love, it’s not the kind of story that I want to spend countless hours imagining myself in.

I said above that it’s important to have answers to The Big Three Questions as you set out, but you need to allow them to change. There will likely come a point where you’ve implemented a good solution to one of them, try it out and realize that you don’t actually like how it effects things.

A Personal Aside

Years ago I read some Banana Yoshimoto books, that absolutely changed me. Her works are fascinating to me because they’re rarely about anything, and yet you keep turning the page to see what happens next. The ones I read were slice-of-life stories about completely normal people having normal lives, with the tiniest hint of magic at work in the world.

Her books are like the Matrix: “Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself.”

If you’re interested in creating a game like this, or a “cozy witchcore”, you should know that Monte Cook Games is currently (May 2024) working on a book specifically about helping you create those kind of stories. It’s called “It’s Only Magic”, and I’m confident it’ll be useful even if you don’t care about the Cypher System.

It’s not for them

When most people write a game they try and keep other people in mind. Don’t. Obviously the final product needs to be something that other people can understand but it doesn’t need to be something they like. The more you try and cater to what other people enjoy, the less interesting and compelling your game will be.

The best thing that happened during the creation of my game was sitting myself down and saying “Fuck that. What do I want?” I intentionally made an incredibly selfish wishlist of things that would be in an ideal game for me. For example, I wanted cards related to character abilities and items, because I have an ADHD brain, and fiddling with a handful of cards with pretty pictures helps me to focus.

It didn’t matter that cards were way more work & expense, or that they’d radically increase the cost & logistics of a game. What mattered was that it was something that I personally cared a lot about, regardless of other people’s feelings on the matter. What mattered is that this list of selfish selfish desires transformed the creative act of game design. I stopped compromising with non-existent people who i didn’t care about. I started making something that would bring me joy. I hope it brings other’s joy too, but the odds of it being particularly memorable are pretty low if it’s filled with compromises.

I’m pretty sure cards won’t be in the final game, but that’s ok. Most of my wishlist items won’t be. Like I said before, you can’t have everything you want in one game. I did try though, and the act of trying to have important things that fit on a card that was mostly picture introduced a critical constraint.

Embrace Constraints

It’s not just that no-one wants to play a game with 50,000 metaphorical levers to pull. It’s not that simpler is somehow better. Constraints focus efforts & keep us on track.

They don’t even have to be topical constraints. For example: “The core rules will fit into 30 pages.” or “There will be no more than 4 pages of spells.” These are great constraints. There’s nothing meaningful about those numbers, but they force certain design decisions. For example, limiting spells to four pages means that either you make a game with a bunch of spells with little-to-nothing in the way of description, or you make one with a very limited but very cool selection of spells.

Topical constraints can be good too though. In ICRPG, for example, you can carry ten items. That’s it. That little constraint means you no longer have a monk walking around carrying a hundred items like the Junk Lady from Labryinth and claiming they can dodge incoming arrows.

Let’s be real, no-one tracks the weight and volume of every item their character picks up.

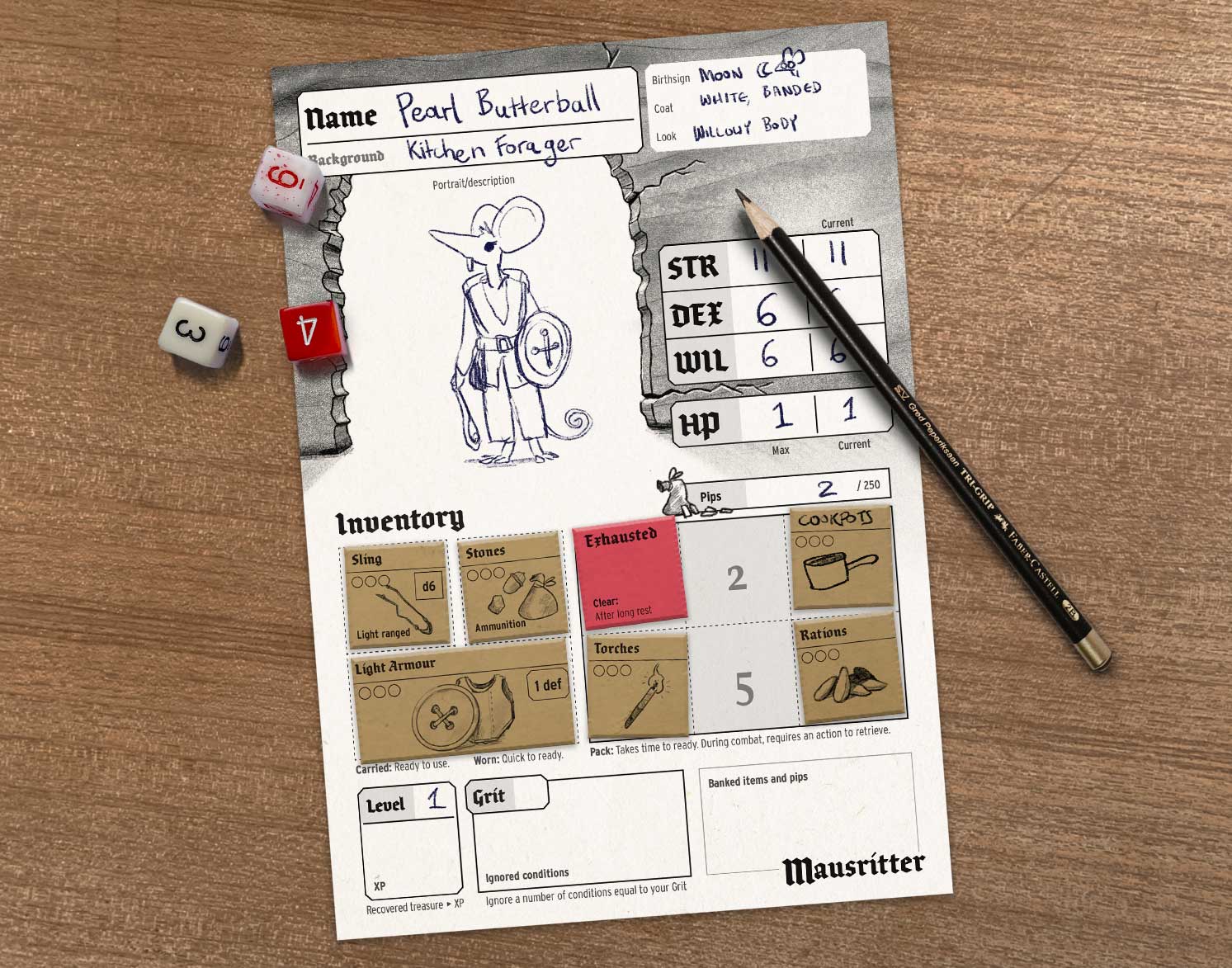

Mausritter took this an additional step, and elegantly accounted for the size or weight of objects by giving you physical cut-outs that you have to fit onto a grid on your character sheet. If you don’t have space, you can’t carry it.

Mauseritter’s inventory constraints tell us that having more things isn’t important, or helpful, to solving the problems you’ll encounter. They way they’re physically implemented, tells us that this is a came that cares about cute little ideas, not nitty-gritty-details.

A game with specific constraints is expressing its opinion about what’s important.

Nothing’s set in stone.

Constraints are great, and wonderful, but sticking to them too rigidly can really hurt too. Maybe you start out trying to write a game that’ll fit in under 30 pages, but along the way you realize you no matter how much you edit away, you can’t convey some of the most critical pieces without more space. That’s fine. Maybe you modify the constraint to be “everything but X in 30 pages”. Maybe you say “30 pages, before layout and images.” Alternately, maybe you realize that you were wrong, and that you’d be doing the game a disservice by restricting the page count so severely.

Trying to work within constraints forces interesting and meaningful game design decisions. It’s valuable even if you learn that that constraint hurts your end goal. Now you know that it’s something important to avoid.

It’s all about the character sheet.

The Character Sheet is the ultimate constraint of your game, because as countless designers have learned, “If it’s not on your character sheet, it doesn’t exist.” There’s too much going on and players will forget and/or ignore anything that’s not staring them in the face.

Needful Things

Your character sheet should provide everything a player needs to take action on their turn. More specifically, your character sheet should answer the question of “what are my options?”

There are two levels to this. The first is “What are the things I know about my character that are actionable?” The second is “What mechanisms does the game provide for me to leverage those?”

Practical Example

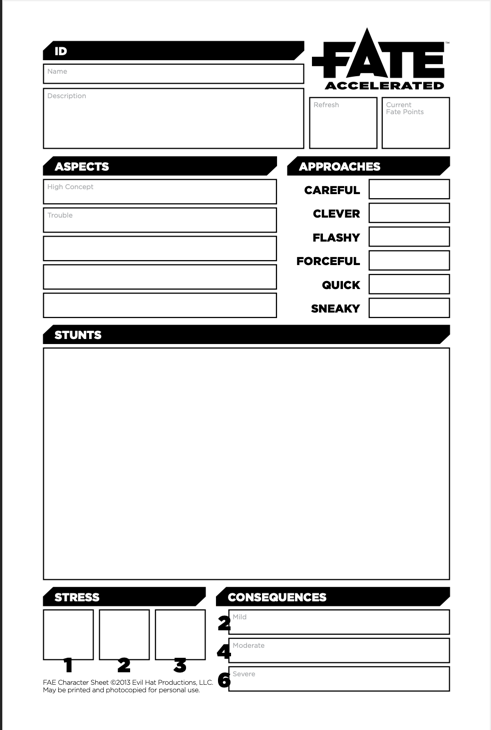

I contend that this sheet from FATE Accelerated succeeds on the first, but fails on the second. Further, I think there’s space to fix that.

It tells us all the important things about our character, and thus answers the first question. It also has some minimal bookkeeping items (refresh, character name, etc) that don’t help us in the moment, but that’s pretty reasonable.

Looking at this though, a new player doesn’t know that at a high level there are only four “Actions” they can perform:

- create an advantage

- overcome

- attack

- defend

It’s damn hard to “sneak” up and “Attack” someone in the middle of an empty field who’s staring directly at you, but it might be pretty easy to act “Sneaky” with them watching you in order to “create an advantage” for someone else.

It’s really important that new players know this when its their turn, but for the GM to be able to set a difficulty for the roll, but also to help flesh out the shared narrative space of everyone at the table.

There’s enough space at the bottom of that sheet for 1 line that says “Turn Actions” and then lists those four choices with a their helpful icons. Or maybe you little flow-chart arrows to guide players through the things they need to consider on their turn. Like first you choose an action, and then follow an arrow that leads you to choose an approach.

Make the character sheet first

The more I iterated on my game, the more I transitioned to a Character Sheet Driven Development (CSDD 😉) process.

With each restart I’d get an idea for what I wanted, then try to shove it all onto the character sheet. This inevitably fails, so then I have to ask myself “which of these things really matters?” Do I need attributes and skills? Do I need to list all the skills? Do I even need skills? Can I maybe get rid of one of those attributes?

I firmly believe that games are always better when their creators have removed every piece of mechanical crap that isn’t necessary to telling the kind of story they want. If you take a Character Sheet Driven Development Process, and you agree that no-one wants to have to reference the book, then you are severely constrained in the number of systems your game can have.

Modify it through play

Make your sheet, define some rules, start playing (see below). Pay attention to what’s missing or confusing on the sheet. Mark up your character sheets to indicate changes as you play. Write in the additional info you wish was there. Next time you sit down to work on it, you’ll have a pre-made list of items with (🤞) all the context you need.

This is inevitably going to have follow-on effects. For example, I use different shapes around things to indicate if it’s a die you roll, or a counter, etc. At one point I’d managed to fit a small visual “key” on the page, but then some change meant I no longer had space for it, but I’m ok with putting reference things on the back of the sheet, so I moved it there.

Later on I came to the conclusion that rolling to see if your shield absorbed any additional damage felt like unnecessary faffing about, especially since my game isn’t even about going and getting into fights. I was able to remove some bits and bring it back.

If you keep needing to look up things that aren’t on the sheet, then your game is telling you you’re either missing critical information, or maybe you don’t need that additional stuff.

Things to keep in mind

In my mind there are a few critical things to keep in mind when putting together your character sheet. I should note that I used to be a Graphic Designer, so there’s a fair amount of hard learned lessons behind these thoughts.

- The more space you devote to something, the more important it becomes in the player’s minds.

- Visual Style matters

- If it doesn’t fit, make space, or throw it out.

- Your character sheet effects if people want to play your game.

- Keep your old sheets.

Visual Style Matters

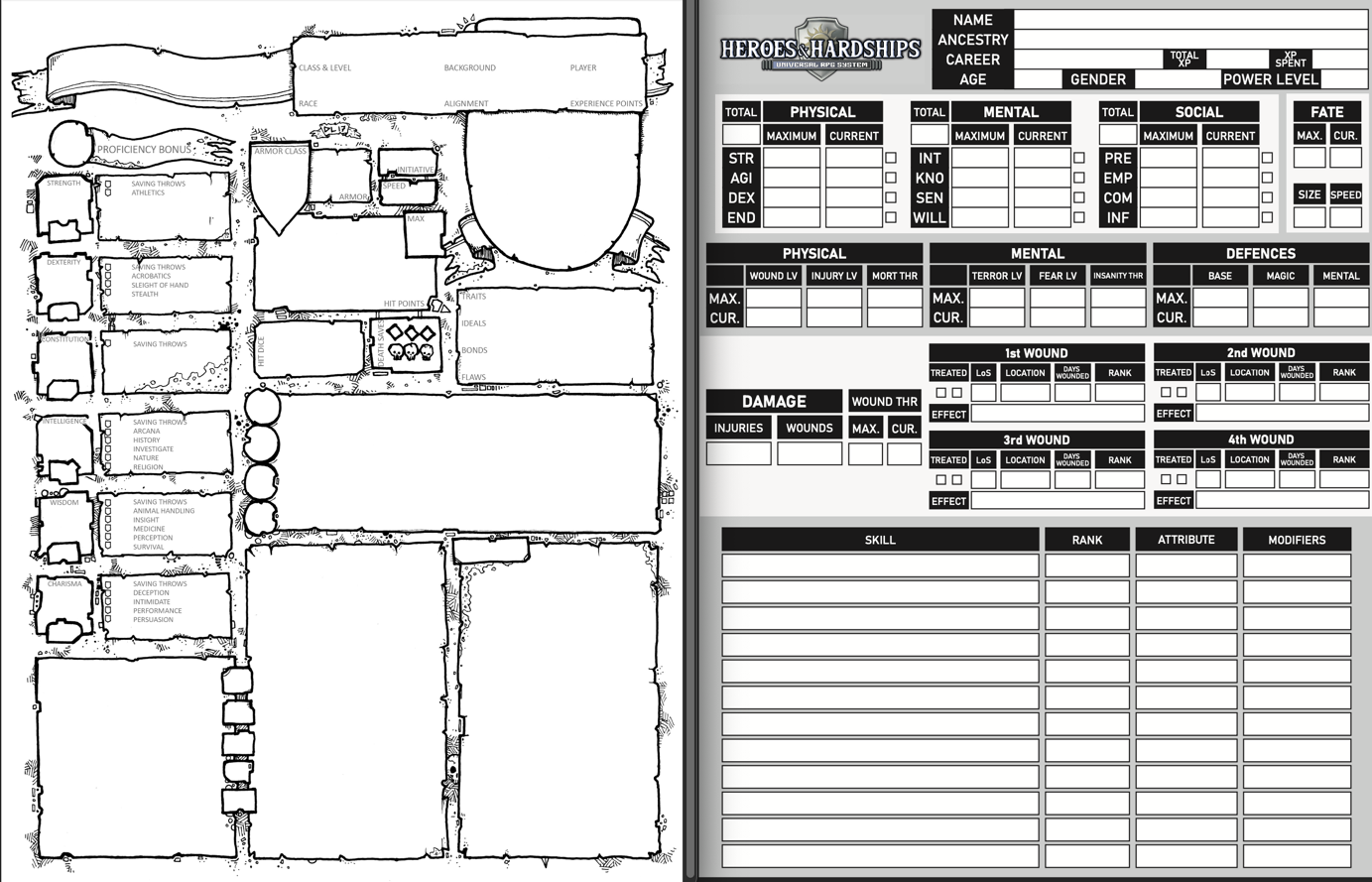

On the Left we have one of Dyson Logos’ takes on a D&D character sheet. On the Right we have the character sheet from Heroes & Hardships5. I’m not trying to pick on H&H, but if you covered up any game name, put these two in front of me, and asked me which game I wanted to play it’d be the one on the left 100% of the time.

It’s fine if you have no visual design skills, and or work with something ugly and spreadsheet-like during game creation. Before it reaches the table though, it must convey tone & help me to know what this game is about. This includes the playtest table. It doesn’t have to be beautiful, but it needs to be better than a spreadsheet.

Don’t make interacting with playtest materials feel like work.

Do I want to play THAT?

It doesn’t matter how cool your game is, if player don’t want to interact with its core elements. I need to interact with the character sheet, but if that looks like a miserable, boring, or annoying experience I’m not going to want to play your game.

If you get me to a playtest, but your core materials suck to look at and work with, and the game isn’t great, then I’m not to playtest it again.

If you give me decent materials to interact with and an ok game, I’ll probably come back to help in the next round.

I actually like the core design in the Heroes & Hardships books, but its character sheets makes me want to set them on fire and run away screaming “YOU CAN’T MAKE ME!!!!”

Make space or throw it out.

That’s pretty much it. If the player can’t determine what their options are and how they can execute on them then you need to make some space for things that can give them those answers.

Unless there’s a way to cheat.

-

Cheating

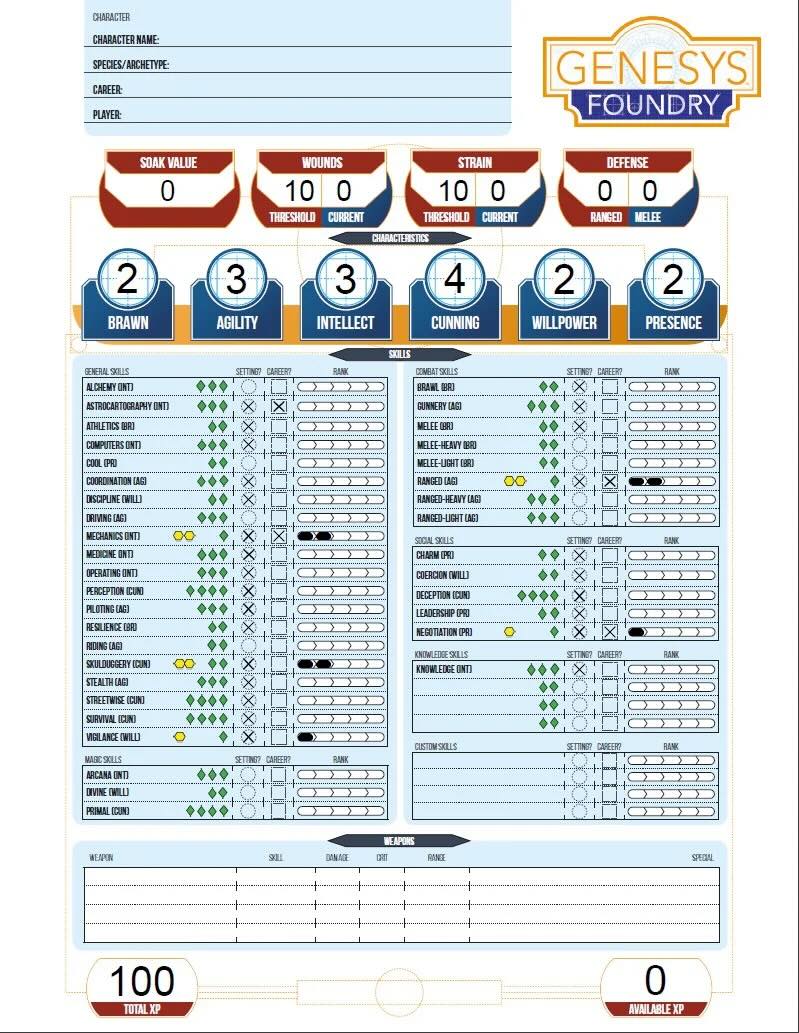

Sometimes cheating is OK. A good example of this is games with long lists of skills, that also limit how many skills you can take. Genesys’ default character sheets are a good example of where cheating wasn’t employed, but should have been.

I find this character sheet maddening, because the character it defines only has 5 skills, but the character sheet has space for 44 skills. Why? Yes, you can gain skills as you go, but you’re never going to get anything close to all of them.

This is a great place to cheat. Figure out what the max number of skills a character can reasonably get is and put in that many blank fields. It doesn’t matter if you game has hundreds of skills to choose from. They never need the full list to play the current session. They only need the ones that are important to them.

Also, Note that there is a column for “setting”. That’s indicating that these are the skills that are available in the current Setting this Generic System is being used for. Never waste space on your character sheet listing things your players can never use.

-

Needful Compromises

Many games allow your character to have a bunch of spells, or special abilities that simply can’t be fit on one side of an A4 / Letter sized page. D&D would be a much worse game if we just threw out spells.

For many games it’s a practical reality that some things will have to go on another sheet. However, the character sheet is dramatically less useful if we remove all relevant info for something critical from the main page.

For example: The official D&D character sheet has a wee slot for common “Attacks & Spellcasting” things, but it lacks the most critical information a spellcaster needs: an indication if it’s even possible for your character to cast anything.

There’s nowhere to indicate how many spell slots you have left. You can’t indicate that one of the “Attacks & Spellcasting” things requires - or doesn’t require - a spell slot. Do you need to be able to move your hands to cast this? D&D’s creators have deemed that all of these questions are important to playing a spellcaster, but I can’t answer any of them without flipping through other pages.

It’s reasonable to move your list of spells off to another page, but it’s not reasonable to force people who play spell-casters to check a second page to know if they can even cast a spell at the moment6. Doubly so when most classes seem to eventually get some sort of resource limited magic or magic-like abilities.

Throw it out if it’s not critical

See those little widgets on the left, for all the different forms of coins in D&D? I don’t know anyone who keeps track of how much change they have in real life. No-one I know wants to make change in some fictional currency they probably don’t remember the subdivisions of.

In early D&D editions, coins mattered because they directly translated into experience points. They don’t anymore, and money rapidly becomes irrelevant in most D&D games. Sure your character might not be able to “afford” the +5 suit of armor, but if that’s the only thing keeping players from getting it, they’ll just murder the shopkeep and take it.

There’s NO reason this valuable space needs to spent on coins when it could have been used to indicate how many spell slots characters had left, or other useful things.

Even if we didn’t have some other critical thing to track, the character sheet would still be improved by simply getting rid of these and allowing a bit more space to list your equipment.

Keep your old sheets

It saves a lot of time. I’m regularly making a tweak to a character sheet and realizing that there was some old version of it that had exactly what I need now. Or, maybe an old version of a sheet you made for some other game.

The more iterations your game goes through, the more interesting these are to browse through. You can see how your values and approach changed over time. Sometimes you even go “oh hey, I liked that thing.” and realize that your game has changed enough that you might be able to bring it back.

Also, keep a sheet with all the visual widgets you create along the way for your sheets. Just a kitchen sink of progress indicators, nifty icons, or whatever.

Accept Defeat

I’ve tooted about Spiral Dice before. I love these things. I desperately want to use them, and I keep trying to use them in this game. It’s taken me a long time to accept that they’re not the right tool for this particular game. It doesn’t matter how much I want to use them. I can’t. At least not here.

There’s a phrase amongst writers: “Kill your darlings.” It doesn’t matter how much you love an idea. It doesn’t matter how much you want an idea. What matters is if the idea contributes meaningfully to what you’re trying to do.

Narrative Dice Are Kinda Broken

There are a few takes on “Narrative Dice”. The most common, or well known use, is to allow rolls to have all of the following outcomes:

- critical success

- success with ancillary complications

- simple success

- tie with ancillary positive effect

- simple tie

- tie with ancillary complications

- failure with ancillary benefits

- simple failure

- critical failure

The Narrative Dice that Fantasy Flight Games created for Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay (3rd Ed), and later reused for their Star Wars, and Genesys games are possibly the best known ones that do this, and I love the core idea. I love how a single dice roll can generate all those possible outcomes. These dice make die rolls into tools for driving wonderfully messy storytelling. At least, in theory.

Once you start to use them, you quickly learn that it’s really hard to come up some ancillary positive or negative side effect for every single test. Like, really really hard. In practice folks just end up using it for the simplest mechanical thing: extra damage on their hit, a bonus to someone’s next roll, etc.

The difficulty of coming up with the “yes, ands” and “no, buts” on every roll completely undermines the promise of dice that help tell the story.

And that’s before we address the fact that the dice are covered with symbols with zero inherent meaning, that players have to memorize and in order to understand which ones are good and which ones are bad, and which cancel out, and which count as two goods vs one good, or whatever.

Two other Options

There are two alternate ways of using Narrative Dice that I’ve seen that are both easy and helpful.

You can do something simple like assigning a color to each factor that contributes to a roll. For example black dice for your core skills, red dice for benefits from weapons, and blue dice for benefits from magic. Then when you roll, you see that you didn’t have enough successes from your core skills, but that the magical dice added just enough to succeed in your attempt. Now you can narrate how you “…lost your footing, and would have missed if not for your companion’s spell guiding your blade.”

The other alternative is what Parable Games has done with Shiver. To over-simplify a tiny bit, there’s an 6 sided die with a bunch of symbols on it. Each symbol’s associated with a skill. For example, a fist for “Grit” (lifting, punching, brute force), a heart with a rose in it for “Heart” (persuasion, deception, charm, etc.). You decide what skill you’re using, roll the relevant number of dice, and see if any came up with the Skill’s symbol. What you see on the dice reinforces the thing you were trying to do. This is dramatically helped by the fact that it’s easy for western players to associate the symbols with the meaning. Fist for punching and strength. A lightbulb brain combo for smarts. A four leaf clover for Luck. They leverage the established meanings of most of the symbols to help support player understanding.

You could just use a 6 sided die and say “When you roll Heart you succeed if a 4 comes up. When you roll Grit you succeed if a 2 comes up.” But that’s a lot harder to remember. It’s an accessibility aid, and a narrative aid. If you tried a wits roll, but failed with a bunch of fists you can look at the dice and say “I didn’t succeed because I tried talking instead of punching”.

Solo Playtesting

I have literally never heard any other game designer talk about doing this, and it is - without question - the most powerful and effective tool in my arsenal.

The idea here is pretty simple. Before you bring your game to anyone else, you will have played dozens or hundreds of sessions with yourself, and Mythic Game Master Emulator (GME). Print out character sheets, make two or three characters using your character creation instructions, sit down at a table and start playing. There is no planning necessary. Literally. Mythic can be your Game Moderator & generate the entire adventure as you go.

Of equal importance is the fact that you can stop at any time. If you stumble over a critical rules problem, or important decision that needs to be made about how the game works you don’t have an entire table of people who either have to go away or have to sit around while you spend however long it’s going to take to fix it.

This means you can iterate so much faster. You can try out half-baked ideas. You can try out that starter adventure, or better yet, generate that starter adventure (see below).

I can’t count the number of times I have put together a core mechanic that worked, that did exactly what I was hoping it would, but either wasn’t fun, or revealed that the bookkeeping required was worse than the gameplay it supported.

It’s key to be very self aware while playing like this. You need to try and notice when you’re annoyed, when you’re bored, and when you’re having fun. The latter is a little harder to notice in the moment, because you get completely immersed in the events that are happening. That’s why you…

Record Everything

The medium isn’t important: video, audio, written on paper, written on the computer, whatever. What’s important is that it’s a medium that is easy and/or enjoyable for you. These recordings are for you alone. You’ll probably never show them to anyone.

As you play you will encounter things that make you realize “oh, I’m going to need a rule for that”. You’ll have thoughts like “Doesn’t Starforged have a tool for this?”. Obviously these things need to be captured somehow, but there are smaller things that are equally important. Things like the die rolls.

When I was in the earlier stages of this process I wouldn’t write down all the die rolls. Later on, I’d want to make a tweak to the mechanic and wonder how it would have effected past scenes. Without the old die rolls recorded I couldn’t say. I’d have to spend time doing another playtest session. I love playtesting my game, but at the moment I just want a quick answer to my question so I can move on.

As you design a game, your focus moves from one area to another. In my experience I’ll wander away from one thing focus on something else, but then have questions like “Does that first thing still hold up with what I’ve changed since then?” “Am I still happy with that?” You can pull out those old records and revisit old decisions from a new perspective. Maybe you swapped a mechanic for a new one, and find yourself questioning the decision. Having recorded playtests means you can easily compare things. Well, “easily” once you find the right place to look.

Obviously, once you get your game in front of other people you’ll want to record that too. If you’re using video (best) or audio recordings remember to ask for consent & make sure they know that it’s just for you to review gameplay things and that you won’t be putting it online.

Example

I prefer good old-fashioned paper. I do a “journaling” style of solo RP where I’m literally hand-writing a story as I go. It’s slow AF, but something about it really works for me. Also, I find it way easier to find a specific piece of information in an annotated text than in a long video.

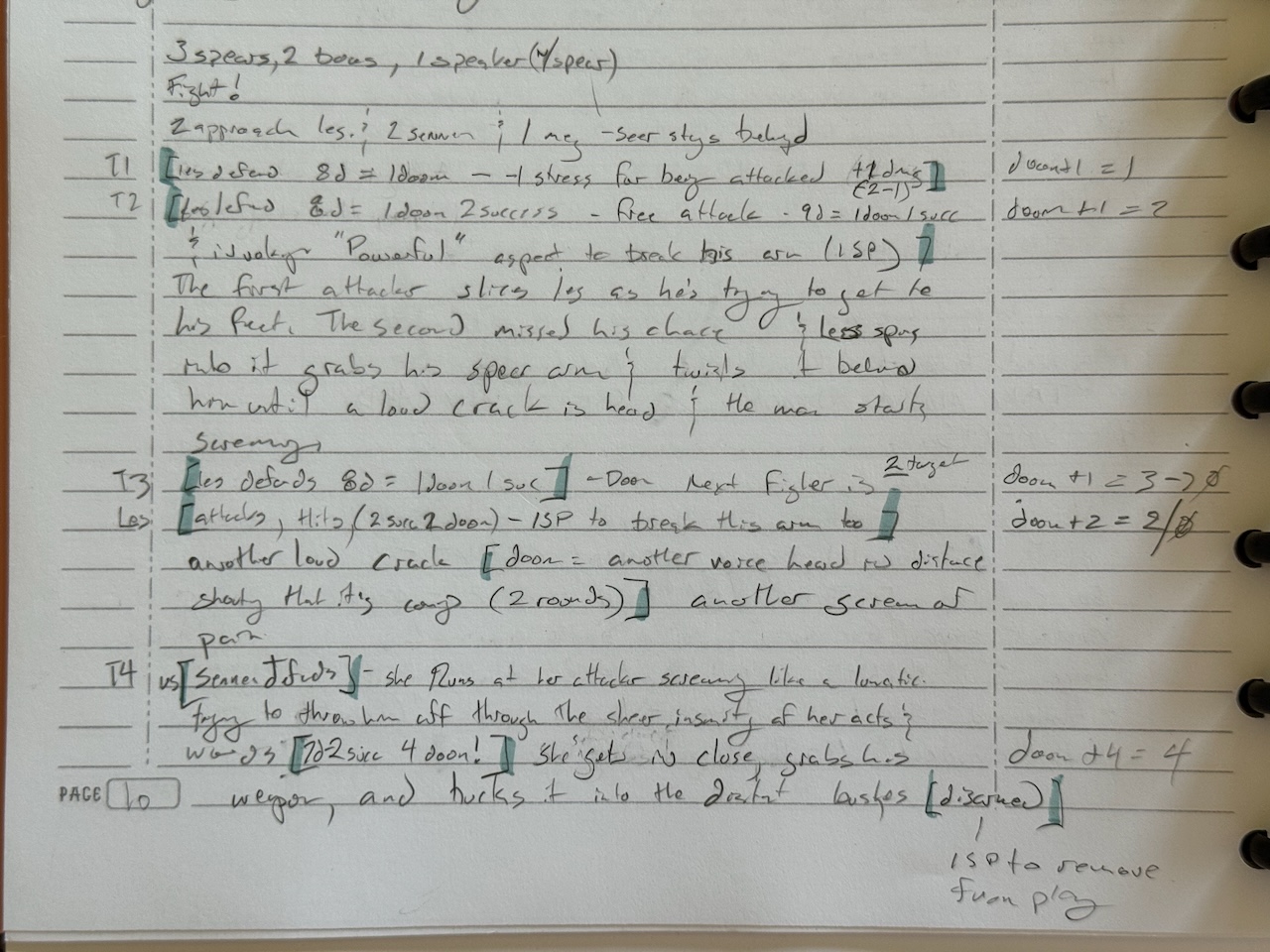

Every single time a die is rolled, I note which character rolled it, why, & what the result was. That sounds a lot more formal than it is. Here’s an example from the combat encounter I mention below.

Don’t worry about trying to read my scribbles. I’ll walk you through it. This record was incredibly useful during the playtest & after.

-

Doom Doomity Doom

In the right column you can see that I’m keeping notes on my Doom Pool7: “doom +1 = 2” & “doom +1 = 3->0”. This was partially because I’ve learned that it’s important to record everything mechanical that happens in this process, but more importantly to me at the moment the fact that my I had a mechanic such that whenever a 1 came up on the a player’s roll Doom was generated, and the GM would roll a die. If the die was less than the current Doom level, some complication would be inserted. This mechanic was “firing off” way more often than I had anticipated & it was becoming a problem.

As I continued to play the side-bar showed me the practical reality of my mechanic and how the numbers changed over time. I was able to clearly see that it’d always be “too much” and that it wasn’t just some bad rolls. I abandoned the “doom” mechanic, continued the playtest and came back to it later.

-

How many rolls

Later on while trying to figure out how to fix my broken mechanic I needed to know how many rolls I could expect in a typical session.

This isn’t a number you can look up online, because not only is it different from game to game, it changes with the GM’s storytelling style or what kind of antics the players like to get into. However, I’d been tracking all the rolls. In the way I record stuff, everything between the blue highlighter lines is either a roll, or “above the table” stuff; the discussions at the table that are about the narrative but aren’t, in the narrative.

I was able to go back through my playtest, scan through all the short blue bars, and count up how many rolls the players would have made over the number of events that I figured would fill up a standard gaming session. In the screenshot above there’s a roll directly after most of the lines with a note in the left column. T1-T4 is indicating which of the unnamed “bad guys” I’m rolling in response to. I don’t remember why I used “T”.

-

meta-notes

One of those notes is “[Doom = another voice heard in the distance shouting that it’s coming (2 rounds)]”. At the table the GM would just say “You hear a shout of support coming from the woods. Another one is coming soon.” I was recording how I adjudicated things when the doom pool was triggered. Sometimes that’s good example material for future GMs. Sometimes that’s a record of how you were struggling, and what was problems you were having.

-

Calculating rolls per session

Knowing the game system is enough to give us a reasonable starting point to work from. If your game’s dice usage is going to be similar to some other game, you can use it as a stand-in until you’ve got enough playtesting of yours.

For example, we know that most D&D combats don’t last more than 10 rounds. We know that players roll on every round, and that it averages out to about a 50% hit rate. So, 50% of the time they’ll also be rolling damage. Most characters get attacked most rounds & (guessing here) 25% of those times they’ll have to roll some sort of constitution or dexterity check.

Assume a 4 player table, and an 8 round fight, and you’ve got some numbers you can work with. On the player’s side we have 32 rolls to hit, 16 rolls for damage, and 8 “check” rolls. D&D tends to have a fight in every gaming session so we can reasonably assume there’s at least 56 player-facing rolls in every session. Round it up to 60 for some out-of combat stuff and we’ve got two useful numbers. Tada 🎉.

Now we can answer the question “how many rolls in an average session?”. For the many games like D&D it’s somewhere around 60 rolls per session, & 15 rolls per player per session.

If you haven’t tried solo role playing

If you haven’t done solo role playing with a “normal” RPG this may sound weird / impossible. It’s not. It’s incredibly easy. If you want to see an example of how this works go watch Trevor Duval’s Me, Myself and Die! Season One8. The first scene is a “chef’s kiss” example of how Mythic GME can tell a story you had no idea was coming.

Side note: Version 2 of Mythic GME is the combination of years of playtesting and learning by tons of players. It’s more refined set of tools, with tons of examples. However, my 🧠 has a lot of trouble extracting the core things you need to do from the descriptive / explanatory text in v2. If you have that problem, Version 1 is the same core ideas in a package that is very “to-the-point” and easy to use.

Generating a Starter Adventure

- Grab the GME, a few characters, and start playing.

- Record what happens as you go.

- Bring it to a satisfying conclusion.

- Take all the “here’s what happened” and convert it to “here’s what could happen” & delete or change any bits that weren’t entertaining enough.

Simple Example:

In a recent playtest 3 characters were quickly making their way through the rainforest to get to an unknown artifact before an opposing faction did. They crossed a perilous ravine, exhausted & happy to be alive. They didn’t realize they’d been watch by a new group of people who moved into the area. While they laid there catching their breath, they were ambushed. Completely overpowered they fought back until they could run for their lives.

Now I have detailed information on 2 separate “encounters” with very different things for characters to do. I’ve got a perilous ravine to cross & I know what that looks like & what environmental troubles & help they’ll have. I’ve got a combat scene that introduces characters to the idea that the only way to survive is to be creative. You won’t be able to murder your way out of every situation.

Solo Playtesting Adventures

While originally designed for emulating Game Masters, Mythic GME can be used as a player emulator. This, obviously can help your playtesting by coming at things from a different perspective, but it also means you can simulate what might happen when players start interacting with a pre-written adventure of yours. Alas, there’s no good way to simulate another GM reading and interpreting the things in your written adventure. You just have to give it to someone, and keep track of the questions and problems they have along the way.

Mythic Magazine volume 41 discusses how to use Mythic GME as a Player emulator.

What else?

There are probably some more important lessons that I haven’t thought of at the moment. Over time I’ll likely update this document with things I forgot, and new things I’ve learned.

I’ve also specifically avoided talking about tools. The tools that work for me probably won’t work for most of you. That being said, I derive a lot of value from seeing the tools other folks use to accomplish tasks. There will probably be a future post going over the tools I’ve put together, and what I’ve found to be useful, or not.

In both cases, if you’d like to hear about updates you should follow my account on Dice.camp

Call to action

This post took a lot of time. If you found any part of it worthwhile, please let me know. My TTRPG Mastodon account is the best way, but email works too ( masukomi@masukomi.org ). My blog posts kinda feel like I’m spending a lot of effort to yell into the void. If you’d like to see more. let me know. Ditto for anyone else creating content online.

-

: Whatever cool generic system thing you’re thinking of doing, please go read GURPS first. I assure you they probably did it, and they probably did it better, and more comprehensively than you were even considering. GURPS has a ton of bad PR about being a “crunchy” game, which turns many people off. It’s not. It can be amazingly low crunch, and there are so many great books for it on so many topics. It’s ugly. It’s old. It’s got far too many character options to choose from, but when you get to the heart of it, it’s a really good generic system. ↩︎

-

: If you’re playing a PbtA game and always using the “default” Move, then it’s either a poorly designed game, or you’re trying to tell a story it wasn’t designed for. ↩︎

-

: The spells in Dungeon Crawl Classics are a thing of beauty. Ridiculous unpredictable things that, even when you roll “successfully”, may or may not get you what you were trying for. Consulting a massive table every time you cast a spell isn’t great, but for the right table it can be ridiculous fun. ↩︎

-

: If you want a simple game where you go around having fun fighting monsters & bad guys, where magic can go wrong and screw everything dramatically, check out Index Card RPG (ICRPG). It has three default settings that are all great. ↩︎

-

Despite what I said about Generic Systems, Heroes & Hardships is a really good Generic system that does a lot of things right, and I’ve got a huge amount of respect for its creator. Alas, I hate that its character sheet looks like a freaking spreadsheet. ↩︎

-

: because someone’s going to try and say it: No, you can’t always cast a cantrip. ↩︎

-

: At its core a “doom pool” is a mechanic that lets the GM build up points that they can later spend to complicate players lives.

If you’re curious what the notation meant: “doom +1 = 2” meant the roll generated 1 doom & “doom +1 = 3->0” meant the roll generated one doom, the total was raised to 3, but then the pool got used and reset to zero. This is just what I was doing on the fly and not a recommendation for anything. ↩︎

-

: Me, Myself and Die! Season One is quite possibly the most entertaining actual play series I have ever watched. ↩︎